For those of you who read my weekly Sunday Newsday columns, you probably would've read

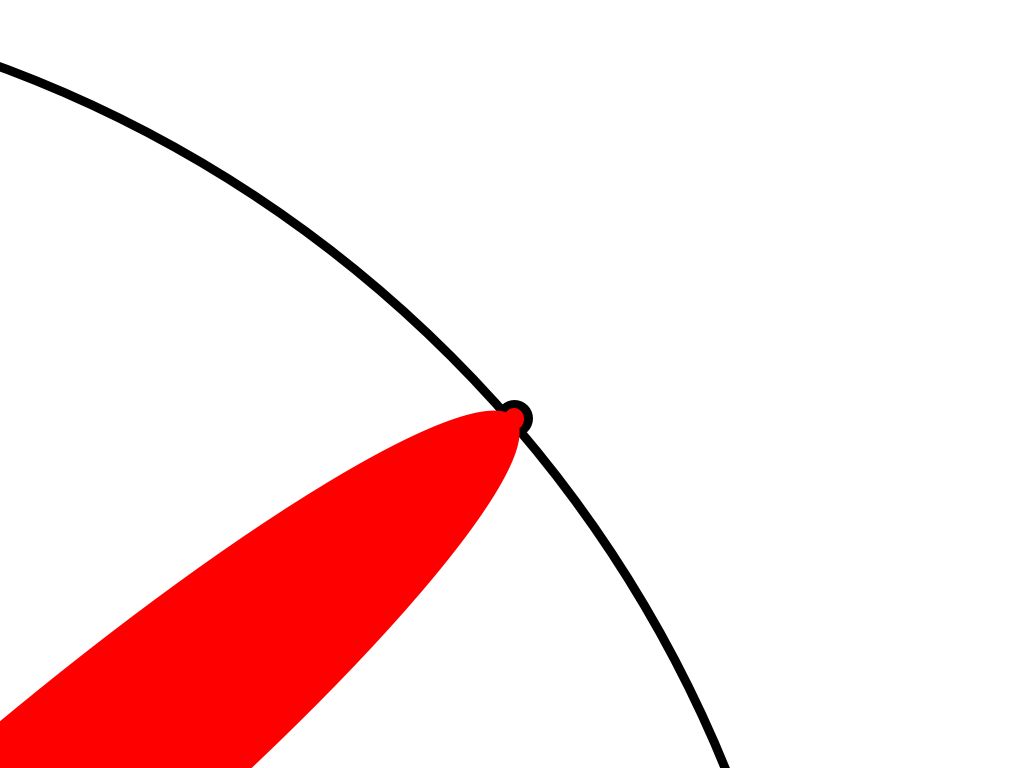

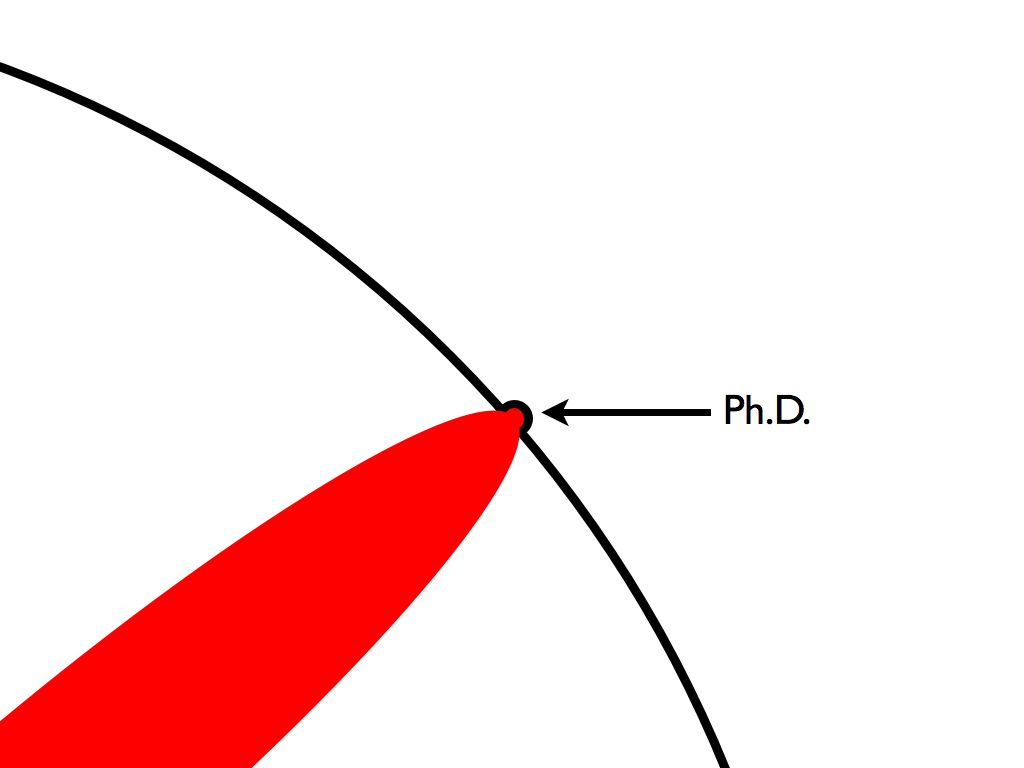

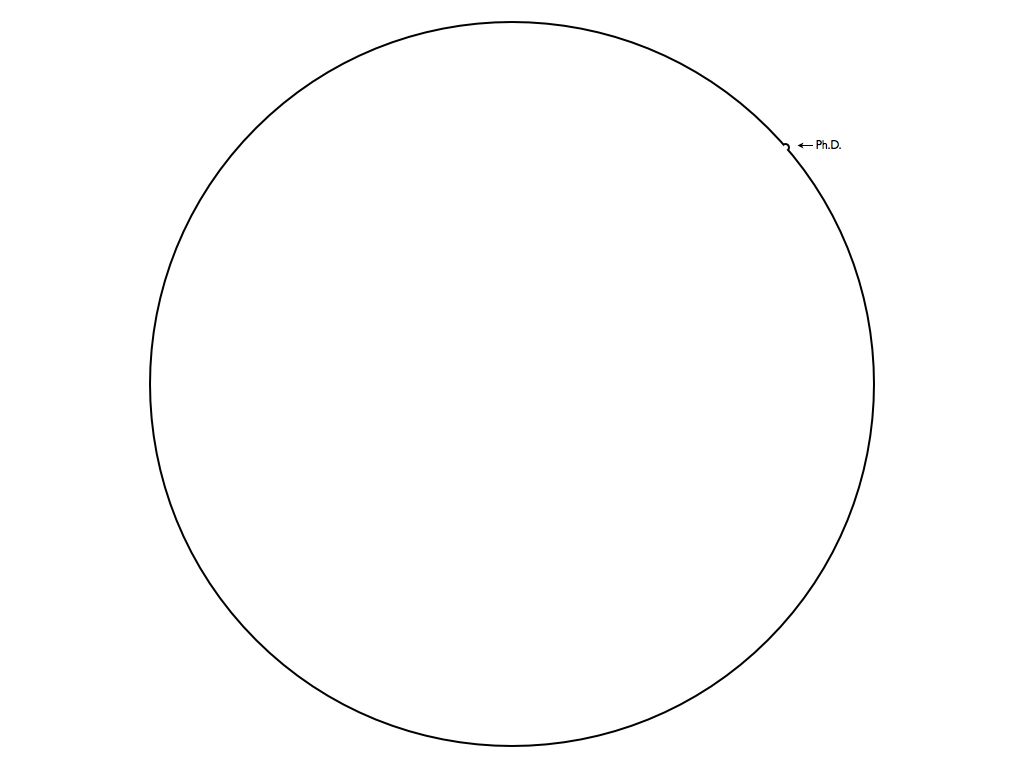

this article, where I expressed my concern with the declining quality of legal professionals in Trinidad and Tobago, especially as a result of the DEFICIENT distance learning education offered by the University of London.

Anyway, on Sunday May 3rd, 2015, a 9-year-old boy jumped into a car and went for a joyride that came to an abrupt end when he crashed into another car. Thankfully, this ended in damage to property and not death or serious injuries to him or anyone else.

Subhas Panday was the main contributor of this nonsense, apparently quoting outdated British law to be applied in Trinidad and Tobago. I say outdated because doli incapax was abolished under section 34 of the

Crime and Disorder Act 1998, and confirmed by the House of Lords in the case of

R v JTB [2009] UKHL 20.

Subhas was confident in his declaration that "the boy is doli incapax in the eyes of the law", stating that the boy could not be held responsible for the offence of larceny because he was under the age of 10.

How this "senior criminal lawyer" (as he was described by the newspaper) could spew this inanity in the public domain is beyond me.

According to section 2 of the

Summary Courts Act 1918, as amended a child is between the ages of 7 and 14 years old. However, as is common in our banana republic, one legislation contradicts another, so according to section 2 of the

Children Act 1925, as amended, a child is said to be ‘a person under the age of fourteen years’.

Subhas' misplaced confidence was even more evident when he said that the question of the child actually committing the offence according to the definition of "steals" under

section 3 of the Larceny Act 1919, as amended "does not even arise" because of doli incapax.

Clearly, he shares the common misconception that the presumption of doli incapax is a defence. Au contraire, the law is clear; the burden is on the prosecution to rebut the presumption in every case, or there is no case to answer. It is NOT an automatic defence.

Also, in the British case of C v DPP [1995] 2 All ER 43 at 62, a further principle regarding rebuttal was that the guilty knowledge "must be proved by express evidence, and cannot in any case be presumed from mere commission of the act."

Further case law highlighted the fact that the starting point for assessing a child's understanding will generally be his/her age and the type of act committed. The closer the child is to 14, and the more obviously wrong the act, the easier it will be to rebut the presumption.

Perhaps the most common form of evidence used to rebut the presumption is what the child says when interviewed by the police. It is also possible, but not necessary, to call an expert witness to give evidence on the child's developmental state.

History of doli incapax:

Doli incapax was said to have originated during the reign of Edward III in the 14th century; however, recognition of the fact that children may not have criminal capacity can be traced back even further to ancient laws, like those of King Ine from 688 AD and King Aethelstan from 925 AD.

This is a British anachronism that they themselves have rejected for almost 2 decades, yet we have our lawyers quoting it and trying to use it to guide our local system.

Instead of dealing with real issues and reforming and implementing legislation to make the legal system clearer and better, our politicians waste time discussing pointless motions of no-confidence in Parliament.